Fool’s Gold Vs Real Gold: How To Spot The Difference

By AAA

March 18, 2022

The glittering golden mineral pyrite, an iron sulfide, is known to most people as fool’s gold, something that promises great value but is intrinsically worthless. But pyrite is, has been, and will be important to you and the rest of humankind. It is the mineral that made the modern world.

This influence extends from human evolution and culture, through science and history, to ancient, modern, and future Earth environments, and the origins and evolution of early life on the planet.

The role of pyrite in fire-lighting is a feature of all ancient civilizations. It led to the development of the modern chemical, pharmacological, and armament industries, in which pyrite continues to play a vital role. Even today, pyrite is still used in the manufacture of sulfuric acid – the most abundantly manufactured chemical on the planet. The production of medicines based on pyrite, such as the alums, paralleled the development of the chemical industry and can be shown to be the origin of Big Pharma, the industrial production of medicines.

Pyrite crystals stand out in nature, and the ancients were naturally curious as to how these were formed. This led to the idea that pyrite formation occurred deep within the Earth and the mineral was brought to the surface by volcanoes. And yet many occurrences of pyrite in nature do not appear to be related to volcanism at all. Pyrite can be found in soils and sediments throughout the Earth as myriads of microscopic crystals. This pyrite is formed by bacteria that remove oxygen from sulfate in the water, producing sulfide that reacts with iron to former pyrite.

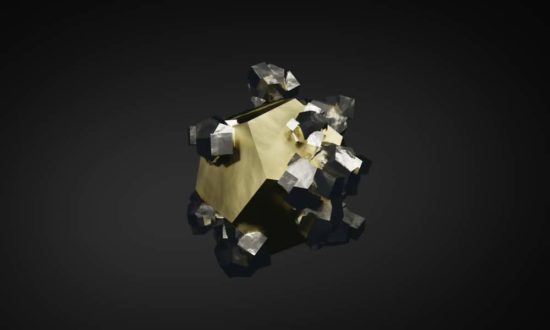

Natural gold tends to be anhedral (irregularly shaped), whereas pyrite comes as either cubes or multifaceted crystals.

Invisible Gold

In fact, pyrite is often associated with gold. The solutions in the Earth that transport iron and sulfur to form pyrite are also likely to transport other metals, including gold. Pyrite is slightly oxidized relative to other metal sulfide minerals. The slightly more oxidized environment in which pyrite precipitates also destroys the sulfide complexes that keep the gold in solution, and the gold precipitates as a metal.

For these reasons, most gold deposits in the world contain pyrite as a more or less abundant mineral. In the case of so-called invisible gold, tiny precipitated gold particles have been trapped in the growing crystals of pyrite. The amount of gold within the grain is probably around 1 percent by weight because gold is about four times as heavy as pyrite. A ton of this pyrite would then contain around 100,000 grams of gold, with a present-day value of more than $400,000. It is worth mining if the gold can be extracted from within the pyrite.

Gold dissolves in cyanide solutions, and more than 90 percent of gold production is based on a cyanide process. In some low-grade ores, the crushed rock is piled into heaps and sprayed with a dilute cyanide solution. After about six months the liquor exiting the heaps carries sufficient god in solution to be collectible. Of course, cyanide is highly poisonous, and although efforts are made to contain and denature it, accidents and escapes continue to occur.

One of the problems with gold extraction is that much of the gold is included within pyrite and related minerals. This means that chemical leachates, such as cyanide, cannot get at the gold because it is protected by the pyrite. In the past, the only way to release the gold was to roast the pyrite at 700 degrees Celsius or to digest it in strong acid in an autoclave at elevated temperatures and pressures.

Both of these processes are very expensive. In 1986 industrial-scale testing of bio-oxidation of refractory gold ores was introduced by Gencor in South Africa. In this process, the crushed ores are initially subjected to the attention of pyrite-oxidizing microorganisms in-tank fermenters. The process exposes more of the gold, and subsequent cyanidation of the bio-oxidized concentrates can result in increases in gold recovery from just 30 percent to more than 95 percent. The use of microorganic reactors to prepare pyritic gold ores for cyanidation has become widespread, and numerous mines in South Africa, Australia, and North America have various operating systems.

The future of bioleaching of ores looks bright as ore grades become poorer and metal prices become higher, and there is a considerable amount of research going on at present into this technology. There is particular interest in the potential of real in situ bioleaching, where the pre-deposit is not mined but fractured and the leach solutions are pumped down. The problem with this idea at present is the difficulty in recovering the solutions – they tend to disappear down fractures in the Earth’s crust, never to be seen again. It seems that whatever the future of this technology, pyrite will be at the heart of it.

The Real Story Behind Fool’s Gold

“Fool’s Gold” is technically known as pyrite or iron sulfide (FeS2) and is one of the most common sulfide minerals. Sulfide minerals are a group of inorganic compounds containing sulfur and one or more elements. Minerals are defined by their chemistry and crystalline structure. Minerals that have the same chemical composition but different crystal structures are called polymorphs.

Pyrite and marcasite, for example, are polymorphs because they are both iron sulfide, but each has a distinct structure. Minerals can also have the same crystalline structure but different elemental compositions, but it’s the crystal structure that determines the mineral’s physical characteristics.

In addition to pyrite, common sulfides are chalcopyrite (copper-iron sulfide), pentlandite (nickel iron sulfide), and galena (lead sulfide). The sulfide class also includes the selenides, the tellurides, the arsenides, the antimonides, the bismuthides, and the sulfosalts. Many sulfides are economically important as metal ores.

Pyrite is called “Fool’s Gold” because it resembles gold to the untrained eye. While pyrite has a brass-yellow color and metallic luster similar to gold, pyrite is brittle and will break rather than bend as gold does. Gold leaves a yellow streak while pyrite’s streak is brownish-black.

Pyrite is so named from the Greek word for fire (pyr) because it can create sparks for starting a fire when struck against metal or stone. This property made it useful for firearms at one time but this application is now obsolete. Pyrite was once a source of sulfur and sulfuric acid, but today most sulfur is obtained as a byproduct of natural gas and crude oil processing.

Today pyrite is sometimes sold as a novelty item or costume jewelry. But pyrite isn’t entirely useless; in fact, it’s a good way to find real gold because the two form together under similar conditions. Gold can even occur as inclusions inside pyrite, sometimes in mineable quantities depending on how effectively the gold can be recovered. Pyrite has long been investigated for its semiconductor properties.

Pyrite is found in a wide variety of geological settings, from igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic rock to hydrothermal mineral deposits, as well as in coal beds and as a replacement mineral in fossils. Pyrite can either be disseminated throughout igneous rock or concentrated in layers, depending on depositional mechanism and environment. Pyrite forms in sedimentary rocks in oxygen-poor environments in the presence of iron and sulfur dioxide. These are usually organic environments, such as coal or black shale, where decaying organic material consumes oxygen and releases sulfur. Pyrite often replaces plant debris and shells to create pyrite fossils or flattened discs called pyrite dollars.

In calcite and quartz veins, pyrite oxidizes to iron oxides or hydroxides such as limonite, an indicator that there is pyrite in the underlying rock. Such oxidized zones are called “gossan,” which appears as rusty zones at the surface. Gossans can be good drilling targets for gold and other precious or base metals.

Pyrite is unstable and oxidizes easily, which is an issue in controlling acid mine drainage in a geological survey. Pyrite is a widespread natural source of arsenic, which can leach into ground-water aquifers when geologic strata containing pyrite are exposed to the air and water, during coal mining for example. Acid mine drainage and groundwater contamination require close monitoring to ensure that it has been neutralized before being returned to the earth.

A question: If you have a shiny and tiny golden color spot in your sample, how would you identify it? Is it gold? Is it pyrite? Portable x-ray fluorescence (XRF) analyzers are an important tool in this effort. In 2-3 seconds, you can identify that black streak grain using a portable XRF. Isn’t that amazing? In addition to being used for exploration and mining applications, XRF analyzers can be used to monitor elemental contaminants at mine sites and in waste streams. XRF analyzers are capable of quantifying a wide range of elements, including sulfur, lead, and arsenic.

Pyrite is distinguishable from native gold by its hardness, brittleness, and crystal form.

Difference Between Pyrite and Real Gold

Pyrite, or what’s commonly known as “fool’s gold,” has tricked countless prospectors into thinking they’ve found valuable gold when they really didn’t. Ever since the early days of the 49s during the California Gold Rush, this metal has broken dreams for thousands of hopeful prospectors.

To the untrained eye, pyrite looks quite similar to gold in the sense that it’s a similar yellowish color, but there are some notable differences between the two. Whether you’re a recreational or professional prospector, it’s important to know and understand the differences between pyrite and real gold. Only then can you rest assured knowing exactly how much valuable gold you’re going home with after a long day of panning and prospecting.

If you’re serious about panning or prospecting for gold, you’ll need to educate yourself on the differences between real gold and pyrite. The fact is that real gold can be worth over $1,700 per ounce, while you’ll be lucky to get a buck for that much pyrite. The bottom line is that you have to be aware of what minerals in your pan are actually gold and which ones aren’t. Trying to sell fool’s gold as real gold can get you into a lot of trouble, but thankfully it’s fairly easy to tell the difference. Just use some of the methods listed below.

Streak Test

Steak tests are one of the most effective methods used to check and see if a mineral is actually gold. If you don’t know what these are, let me explain – streak tests are performed by rubbing a mineral nugget on an unweathered surface known as a streak plate. Once the mineral is rubbed, it leaves behind a colored trail of mineral powder that may give away clues as to what type of mineral it is.

Pyrite typically leaves behind a black-dark green powder, while gold leaves behind a bright yellow powder. You can find streak plates to test for god at dozens of mineral and hobby shops throughout the country, as well as online shops.

Color

After you’ve gained some experience with gold panning and prospecting, you should be easily able to tell the difference between pyrite and real gold simply by looking at its color to see physical properties. Even individuals without any past experience will likely see a noticeable difference between the two minerals when they are placed side-by-side.

Pyrite has a darker yellow color to it that’s similar to brass, while gold has a vibrant yellow color that’s highly reflective to the surrounding light. Holding a piece of gold under the light will reveal a bright yellow color that’s stronger than the dull yellow color of pyrite. Until you’re able to easily identify gold, you should keep a piece of pyrite in crystal form around in your pocket to compare your finds with.

Shape

The shape of pyrite nuggets is something that’s quite unique and not found with traditional gold. Nearly all pieces of pyrite are formed into the shape of crystals, some of which may have nearly half a dozen pylons coming off the base. Of course, this may be hard to see in smaller pieces of pyrite, as the crystals will be small and hidden as well. Gold, on the other hand, is never formed as crystals, but instead, it’s formed as nuggets and small flakes with little-to-no symmetry.

Weight

You probably know by now that gold is one of the heavier naturally-occurring metals found. After all, the entire principle of panning for gold is to wash away the lighter minerals and allow the heavier ones, such as gold, to sink to the bottom. Well, pyrite weighs much less than gold, and small flakes of it usually wash away when placed under the water. Large nuggets may still be left behind, but you can identify these by looking for the crystal-like shape and structure.

Origins of The Fool’s Gold Saying

The early exploration of the New World was under the massive influence of the quest for gold, precious stones, and other riches the new colonies could offer. Martin Frobisher was a famous pirate that built a reputation for attacking and looting Spanish ships in the Atlantic. He was so good at his job that even Queen Elizabeth took notice.

He was quickly drafted into the Royal Navy and tasked with a mission to look for the elusive Northern Passage to China in 1576. His mission took him to the Baffin Island near the Arctic Circle, where he thought he found China. After being kidnapped by the Inuits, Frobisher managed to steal some ore samples that resembled gold and then made his way back to England.

The Queen’s experts examined the ore, and the final verdict was that it was worthless fools gold. Ironically, the story of fool’s gold mission and Frobisher did not end there. The hunger for gold was so powerful at the time that the Queen’s court persuaded themselves and the Queen herself that it was indeed a low-grade gold ore, and they even found a new expert to confirm it.

They provided Frobisher with more ships and men to establish a mining operation on Baffin Island. Frobisher made two more trips back to England, carrying thousands of tons of the mysterious ore. Each of the shipments was worthless, as the ore was mineral pyrite, not precious metal gold.

Ever since the saying “fool’s gold” has been a part of the English language, used to describe something shiny, flashy, or greatly-desired but has no real value. The saying fool’s gold went mainstream during the famous gold rushes in the USA, where plenty of prospectors saw their dreams of fortune disappear by running into pyrite.

Conclusion

Before getting to the practical advice on how to tell pyrite and gold apart, it is essential to mention how pyrite and gold differ on a structural level. Gold is a metal of golden-yellowish color, found in a pure state in nature. Due to its rarity, attractive appearance, and shine, gold is frequently used to create jewelry or other decorative elements. Gold also found its way into currency, as most of the early high-value coins were silver or gold. Later on, gold became a part of the Gold Standard, a monetary system where the value of a country’s currency is directly linked to gold.

Iron pyrite is not a metal but a mineral. It is an iron-sulfide with a brass-yellow color. Often found in sedimentary and metamorphic rock, pyrite is a widespread mineral. The resemblance to gold is quite close, especially to inexperienced eyes. The distinction is even more difficult since pyrite and gold are often present together in rock formations, creating even more confusion.